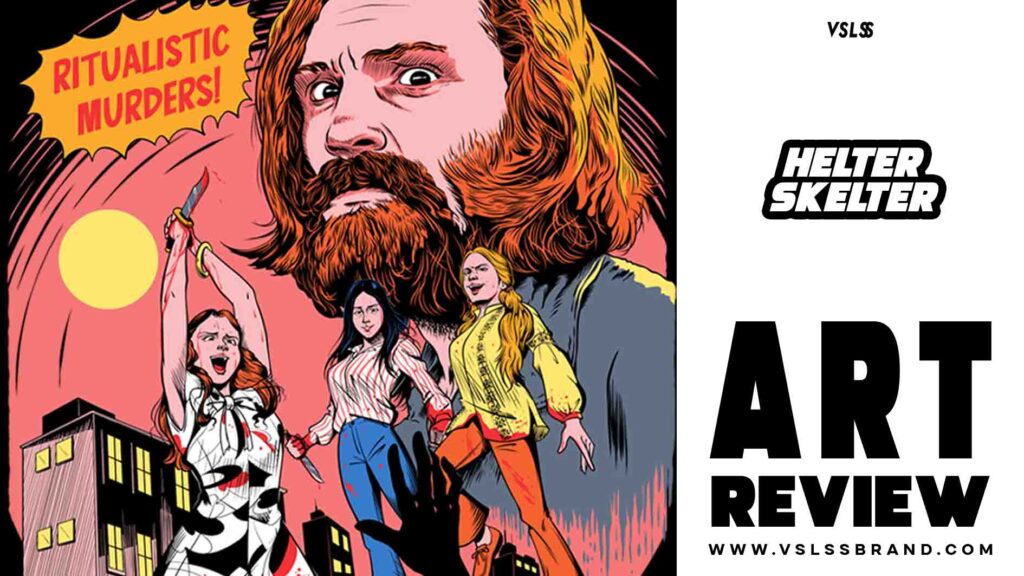

Under the eerie glow of a blood-red sky, a giant figure looms — his eyes wild, his presence inescapable. It is Charles Manson, not as a man, but as a myth, a looming godlike shadow over the chaos he created. Around him, his devoted followers — young women — march through the night with knives in hand, their faces painted with a terrifying mix of joy and fanaticism. The scene bleeds with color, yet it tells a story darker than the deepest night.

They were once ordinary girls. Daughters. Dreamers. But under Manson’s spell, they were transformed into soldiers of his delusion. He called it Helter Skelter — a prophecy, he claimed, whispered by The Beatles, of an impending race war that he and his “family” were destined to survive and rule over. To spark this apocalyptic vision, he ordered them to kill. Not out of hate, but out of “purpose.”

And so they did — gleefully, ritualistically. Not just murdering bodies, but innocence, morality, and reason itself.

This artwork captures that descent — not with gore, but with symbolism. Manson’s face hovers above like an omnipresent deity, while the women below dance through the city streets, knives dripping, framed in a surreal palette of pop-art style. It feels almost too vivid, too colorful for the horror it represents — and that’s the point. The piece forces us to confront how evil can wear a smile, how manipulation can disguise itself in music, community, and even love.

It is not just an image of the past. It is a warning. A reminder of how quickly charisma can become control, how easily belief can blind, and how fragile the boundary is between devotion and destruction. This is Helter Skelter — not just a phrase, but a fall. A descent into madness masked as meaning.